While the Keynesian School of Thought is famous for its rivalry with the Austrian School, I will mainly be presenting critiques of Keynesian Fiscal and Monetary Policy from the perspective of the Chicago (Market Monetarist) and Neoclassical Schools.

A name that will appear quite often in any piece outlining the failures of Keynesianism is that of Milton Friedman, Nobel Laureate and founder of Monetarism, known primarily for his works on monetary theory.

Criticism of Keynesian Monetary Policy, specifically the failures of the Federal Reserve’s long-term targeting of the Phillips Curve.

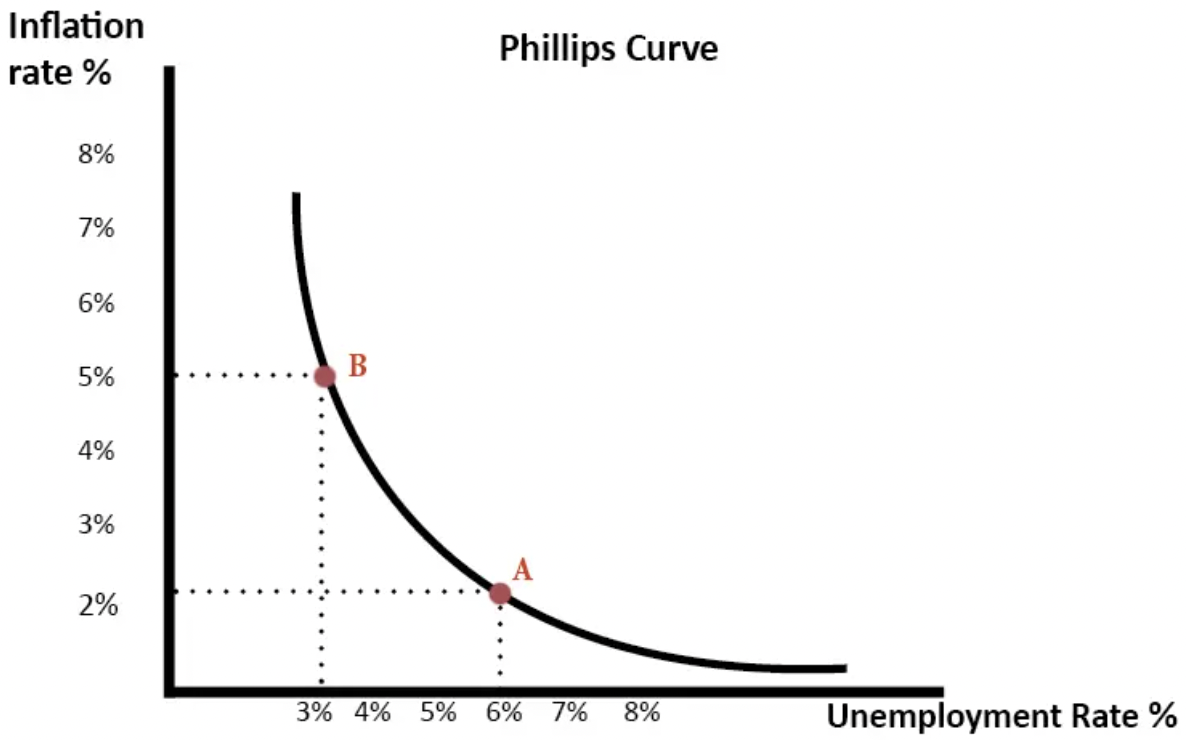

To recognize the shortcomings and long-term failures of the Phillips Curve, it must first be understood what the Phillips Curve is and why it works in the short run. In essence, the Phillips Curve is a Keynesian model which purports to show a negative correlation between inflation and unemployment (Figure 1); this principle carries (or “carried”, as we shall soon see) substantial weight in the monetary policymaking performed by the Keynesian Federal Reserve of the 1960s and 1970s; the use of the Curve in Monetary Policy, however, has fallen under attack in later times, notably among the Monetarists and economists of the Neoclassical and Chicago Schools of Thought.

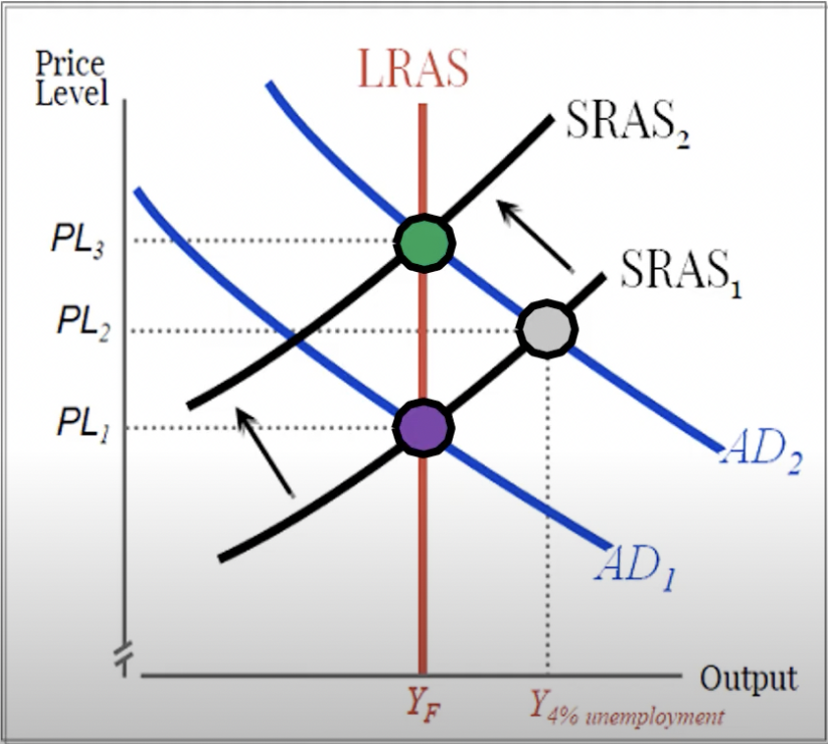

The relationship between unemployment and inflation shown in the Phillips Curve works in practicality solely because of Aggregate Demand and how low or high Aggregate Demand influences one measure to rise at the expense of the other; the success of the Phillips Curve being entirely reliant on Aggregate Demand, however, is one of the failures of the curve, and one which caused the Monetarists and Neoclassical economists to believe that the relationship between unemployment and inflation shown in the Phillips Curve is nothing more than short-term; in the long-term, it is very possible to witness a rise in inflation without a corresponding fall to unemployment.

Inflation Expectations

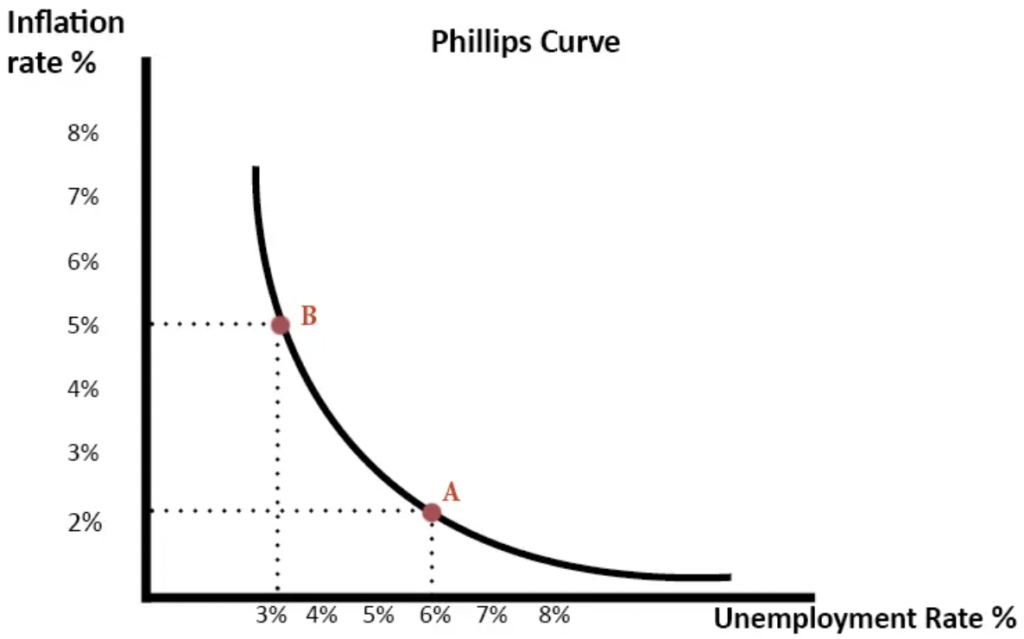

It was previously explained how high inflation would lower unemployment solely because the initial high Aggregate Demand that raised inflation would also serve to increase demand for labor and thus raise employment. This begs the question, however, of the effect high inflation would have on unemployment when the underlying cause is not Aggregate Demand. This brings us to the first major Monetarist Critique of the long-term targeting of the Phillips Curve, that of Inflation Expectations. Inflation Expectations presents the idea that it is thoroughly possible for prices and inflation to rise without raising Aggregate Demand, and thus without lowering unemployment, when, due to a pervasive increase in demand, such as through the excessive monetary targeting of the Phillips Curve, there is a steady rise to the inflation level; in the long run, this will cause workers to expect future inflation, demand an increase to price growth, and raise labor costs, resulting in cost-push inflation without a consequent fall to unemployment for the reason that there is no excess Aggregate Demand (Figure 2).

Once Expectations come into play, accelerating prices follow. This is due to the Wage-Price Spiral: The initial inflation Expectations which caused cost-push inflation would once again provoke Inflation Expectations and cause rising labor costs, once more pushing the inflation rate up even further; this continues, becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy and accelerating prices until the use of a contractionary monetary policy is utilized to bring the accelerating expectations to an end.

For these reasons, the Monetarists argue that the Phillips Curve fails in the long run: While the Federal Reserve is capable of exploiting the Phillips Curve in the short-term and pushing down unemployment at the cost of raising inflation, in the long run, due to Expectations setting off the wage-price spiral, prices will accelerate and the inflation level will rise continuously without a subsequent fall to unemployment; hence, the Phillips Curve will shift upwards in the event of monetary stimulus, with rising inflation and stagnant unemployment, in contrast with the unemployment and inflation variables shifting along the original curve, as was thought by Keynesians.

The role of Expectations on a non-NAIRU (I will explain NAIRU in the next section) level of unemployment on the Phillips Curve can be summarized in an assertion by Charles Goodhart, an economist at the LSE: “Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes”; this statement is now known as Goodhart’s Law. It can be applied directly as a criticism of the Phillips Curve: Through excessive targeting of the Phillips Curve, a statistical correlation, as a means of lowering unemployment, in the long run, the correlation expressed in the curve becomes less reliable and fails to materialize, as is explained by Milton Friedman’s Inflation Expectations.

NAIRU

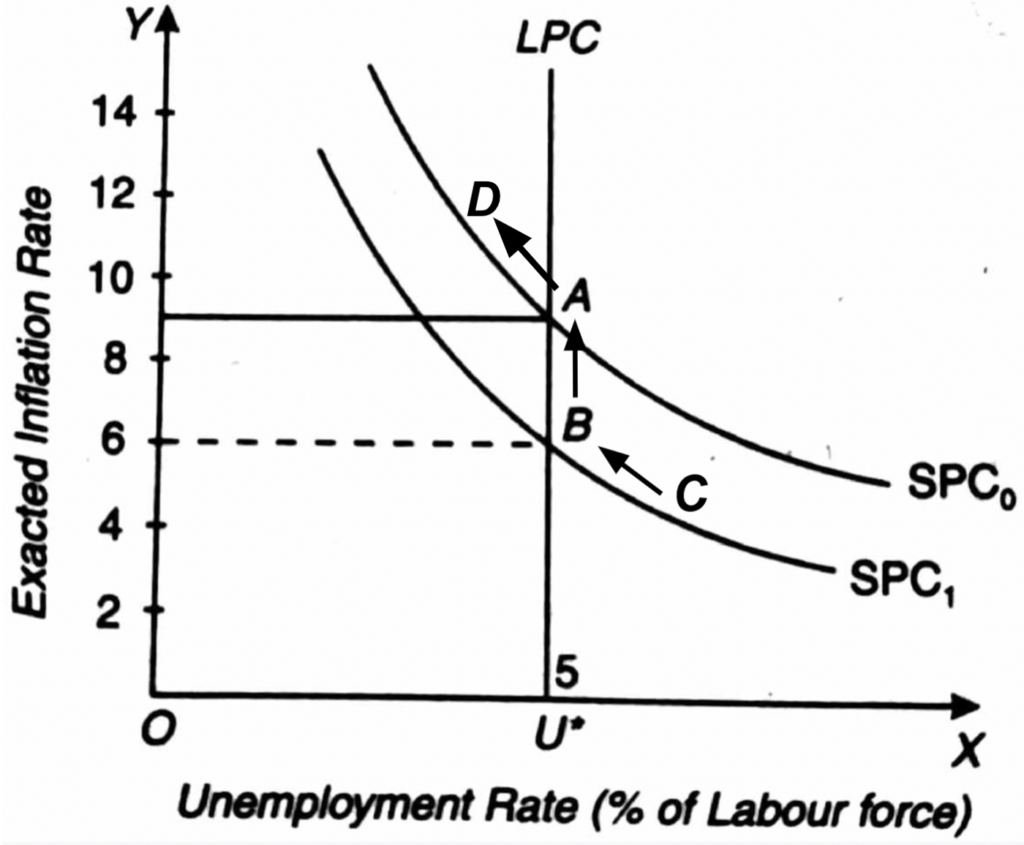

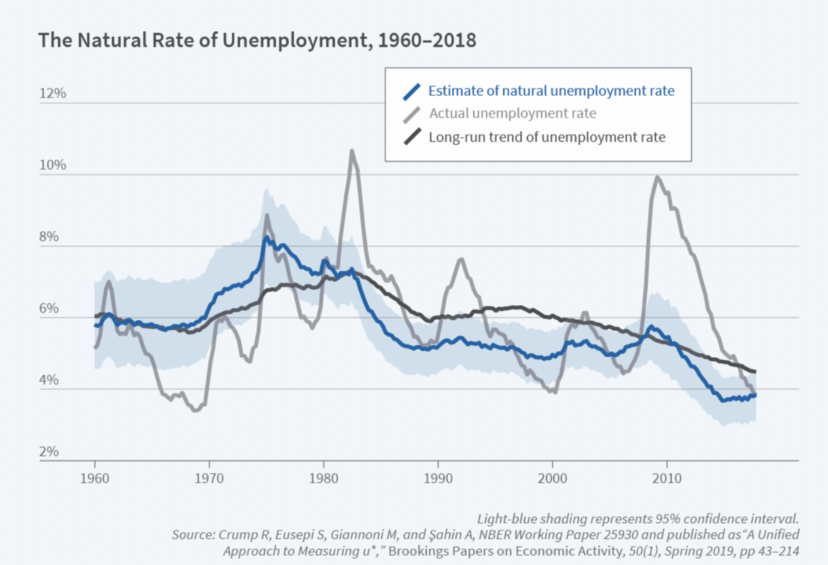

The role of Expectations is expanded upon in Milton Friedman’s 1968 paper The Role of Monetary Policy, in which he, along with Edmund Phelps and other faculty at the University of Chicago, introduced the concept of NAIRU, the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (used interchangeably with the “Natural Rate of Unemployment” or “Non-Cyclical Unemployment”), and asserted that, once unemployment fell to NAIRU levels, any monetary or fiscal policy designed to stimulate aggregate demand and raise employment will fail to, in the long run, reduce the structural and frictional unemployment purely present at NAIRU; instead, it will only serve to raise wages, the cost of labor, contributing to cost-push inflation and an upwards shift of the Short-Run Phillips Curve (Figure 3).

In the end, Milton Friedman’s ideas, that of Inflation Expectations and the NAIRU, led to a complete restructuring of the Phillips Curve into the new Long-Run Phillips Curve Model, the one commonly used today (Figure 3), with multiple upwards-shifting Short-Run Phillip Curves, and a vertical line, the Long-Run Phillips Curve, at the NAIRU to represent the inelastic lower bound of unemployment.

The Long-Run Self Adjustment Mechanism

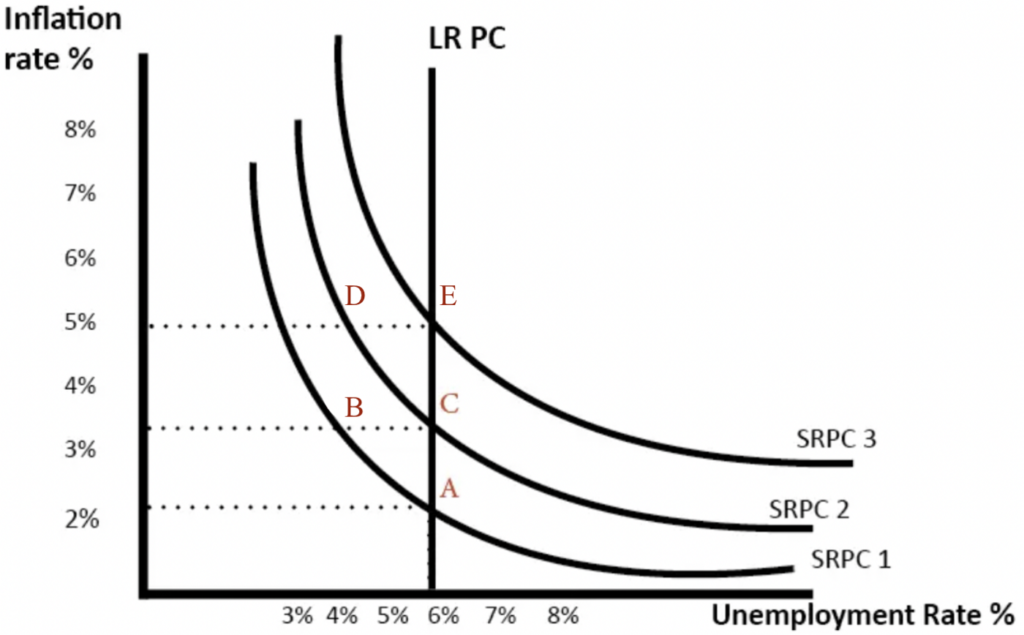

Although the aforementioned attacks against the Keynesian Phillips Curve were directed by economists of the Monetarist School of Thought, the Neoclassical School also called into question the reliability of the Phillips Curve through the development of the Long-Run Self Adjustment Mechanism.

It should be noted that the Mechanism theory is demonstrated not on the Phillips Curve plane, with unemployment and inflation on the x and y axes, respectively, but is instead demonstrated on the AD-AS Model (Figure 5), with Price Level on the y-axis and Output (used interchangeably with Production or Real GDP) on the x-axis; economists do, however, often replace Output with Unemployment, especially in the context of relating the Mechanism theory to the Phillips Curve, with the reasoning that output directly causes demand for labor which in turn heavily influences unemployment. For that reason, this graph uses Unemployment on the x-axis instead of the standard Output, with the unemployment variable decreasing from left to right.

With this knowledge, it is recognizable how the Long-Run Self Adjustment Mechanism theory serves as a direct refutation of the belief that the Keynesian Phillips Curve holds long-term. The Mechanism theory holds that, in the event of a monetary positive demand shock that attempts to stimulate RGDP and lower unemployment, the Aggregate Demand shifts to the right, bringing the equilibrium away from the Long Run Aggregate Supply and increasing prices, short-run quantity demanded, and by extension short run production as supply attempts to “catch up” with the higher Aggregate Demand; this will increase the RGDP, the short-run production, above the Potential GDP, the sustainable production level, opening up an Output Gap. This fails, however, to make up for the demand shock and only serves to raise prices further as the high RGDP surpassing the Potential GDP strains and far exceeds the sustainable supply of labor and resources, placing heavy demand on those two markets and driving down unemployment beyond the NAIRU, as well as placing upwards pressure on labor and resource prices; these rising prices then drive up production costs for businesses while simultaneously drive down demand for resources and labor, raising unemployment back to the NAIRU. Businesses are then forced by the higher production costs to lower production (and by extension supply) and raise prices further (Figure 5).

The essential distinction between this Mechanism and any other natural market correction, however, is that the higher prices, generated by the initial Positive Monetary Demand Shock and by increased labor and resource prices which in turn drive up Production Costs, are embedded into the long-term economy; this is due to how any market measures that attempted to bring prices down, such as higher production and a higher Short-Run Quantity Supplied, were temporary and could not be sustained above the Long-Run Aggregate Supply; furthermore, it was demonstrated that such corrective measures, which strain the resource and labor market, only serve to raise prices even further.

In this manner, the Neoclassical School argues that attempts to stimulate demand and production beyond the Long-Run Aggregate Supply, or, in a similar vein, stimulate unemployment to fall below the NAIRU, would, due to how the Long-Run Aggregate Supply and thus the NAIRU unemployment are perfectly inelastic, fail to increase production or lower unemployment in the long run and result in nothing more than higher prices (Figure 5).

Conclusion of Monetary Policy

The Monetarists’ and the Neoclassicals’ research, namely that of Inflation Expectations, NAIRU, and the Long-Run Self Adjustment Mechanism, provided a serious challenge to the accuracy of the Phillips Curve and the Federal Reserve’s Keynesian approach to Monetary Policy. By extension, these critiques attacked the Keynesian School’s dominance in economic policy, which had gone uncontested and unquestioned for decades.

Their critiques on the failures of the Curve and the correlation it describes would prove prophetic, as no more than two years after Friedman published The Role of Monetary Policy, the Stagflation of the 1970s, the worst Recession since the Great Depression, set in; it was driven by precisely what Friedman and the Monetarists warned about: faulty Keynesian Monetary Policy that excessively exploited the Phillips Curve.

This recession, which will be explored in due time, simultaneously witnessed high inflation and unemployment, something though impossible by Keynesians who maintained confidence in the Phillips Curve; it was only definitively elucidated by, and, as will be explained, solved, by Milton Friedman’s Monetarist ideas. In the end, the ideas set down by Milton Friedman and various other economists of the Monetarist and Neoclassical Schools brought an end to the Phillips Curve and, for once in decades, directly opposed the supremacy of the Keynesian School of Economics.

The Stagflation of the 1970s.

The Stagflation of the 1970s was the single event with the most significant impact on Keynesian thought. Where previously Keynesian principles were the sole force in monetary and fiscal policy, a restructuring of economic thought took place as a result of this event, giving rise to the Monetarist and New Classical (a subset of the Neoclassical) Schools of Economics. It highlighted Keynesian failures, namely the Short-Run Phillips Curve, and served as a major empirical affirmation for the monetary criticisms I have expounded above.

Their critiques on the failures of the Curve and the correlation it describes would prove prophetic, as no more than two years after Friedman published The Role of Monetary Policy, the Stagflation of the 1970s, the worst Recession since the Great Depression, set in; it was driven by precisely what Friedman and the Monetarists warned about: faulty Keynesian Monetary Policy that excessively exploited the Phillips Curve.

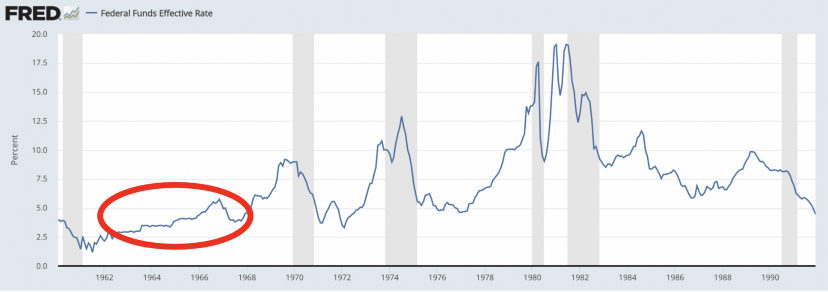

For decades, the Phillips Curve was held to show a solid, inverse correlation between inflation and unemployment; this tradeoff was exploited constantly by the Federal Reserve which relied on the Phillips Curve as a basis of monetary decision-making. The Federal Open Market Committee were, at the time, fixated on lowering unemployment, leading them to be called “Unemployment Doves.” Thus, the Curve presented them with a simple tradeoff, to lower unemployment by raising inflation; this was why, throughout the 1960s, the Federal Reserve engaged in extremely expansionary monetary policy through the lowering of interest rates, the lowering of reserve requirements, and through engagement in Open Market Operations (Figure 3); their reasoning was that although such measures would raise inflation, it would, as the Phillips Curve held, lower unemployment, which they believed to be a bigger concern.

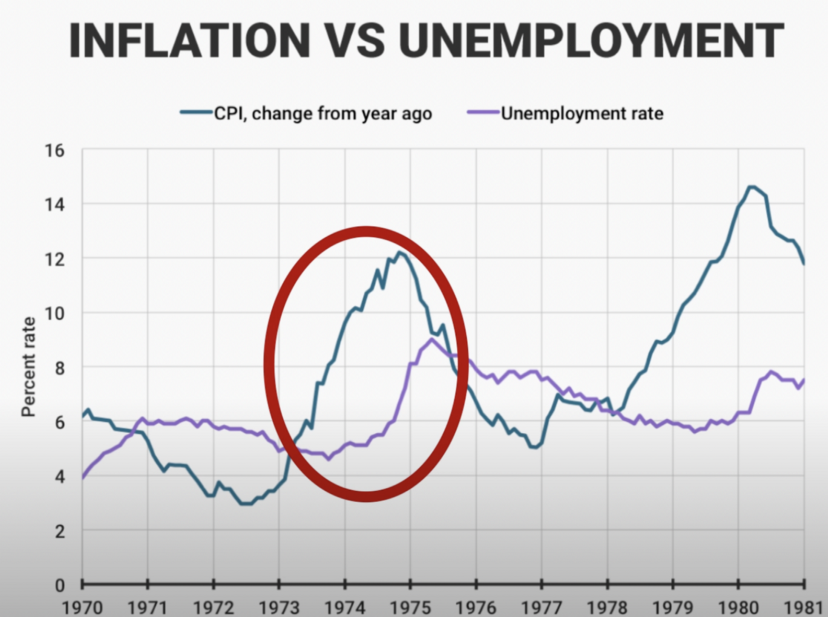

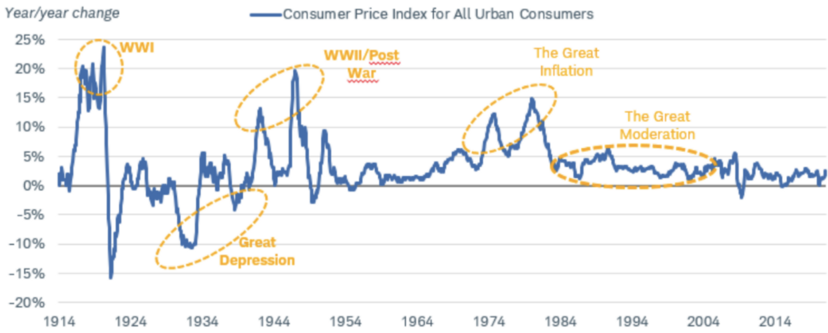

The failures of this expansionary policy, however, became fully visible by the 1970s. As shown in Figure 7, with a combination of both rising inflation and high unemployment, a complete breakdown of the Phillips Curve’s supposed correlation occurred in the 1970s and early 1980s. Such a scenario was thought impossible to Keynesian economists, who were at a loss trying to explain such a phenomenon. Some Keynesians have pointed fingers at the OPEC Oil Embargo (itself with roots in America, when Richard Nixon took the U.S. Dollar off the Gold Standard, putting into question the stability of the Dollar, but I digress), which quadrupled the price of oil; Keynesians claimed that these high prices caused cost-push inflation in major sectors of the economy while simultaneously hurting demand in the labor industry, thus causing unemployment. Although this undoubtedly had an effect, it was not the main cause as evidenced by the fact that other countries heavily reliant on OPEC Oil Imports, such as Germany or Switzerland, weren’t hit nearly as hard with inflation, experiencing at most only around 5% to 6% inflation.

With the Keynesians failing to explain such a phenomenon, Milton Friedman, a Nobel Laureate from the University of Chicago, rose into prominence, arguing that this Stagflation was caused solely by the failure of the Federal Reserve, or, in his words, that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” (demonstrated empirically in Figure 12). He recognized the failures of the Phillips Curve and asserted, through the introduction of NAIRU, which was previously discussed, that it is thoroughly impossible to lower long-term unemployment below NAIRU levels through any economic policy, monetary or fiscal, that increases aggregate demand; instead, such a discrepancy between aggregate demand and labor supply would result in rising wages and cost-push inflation.

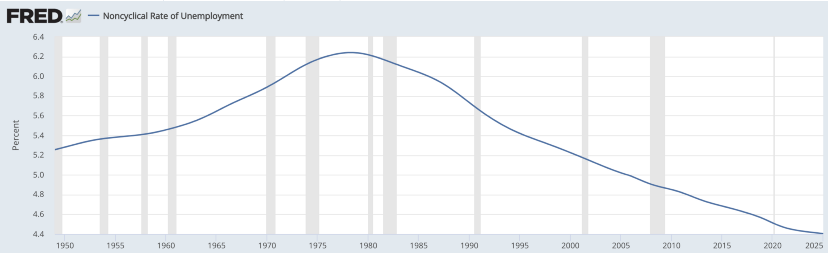

This argument is evident from data gathered in the early 1970s which suggest that, due to changes in the labor market, structural and frictional unemployment rose, raising the estimated NAIRU (Figures 8 and 9) and thus rendering the Phillips Curve unreliable at a higher level of unemployment; essentially, even at a higher level of unemployment, prices will accelerate and the rising employment will stagnate if monetary stimulus attempts to lower unemployment.

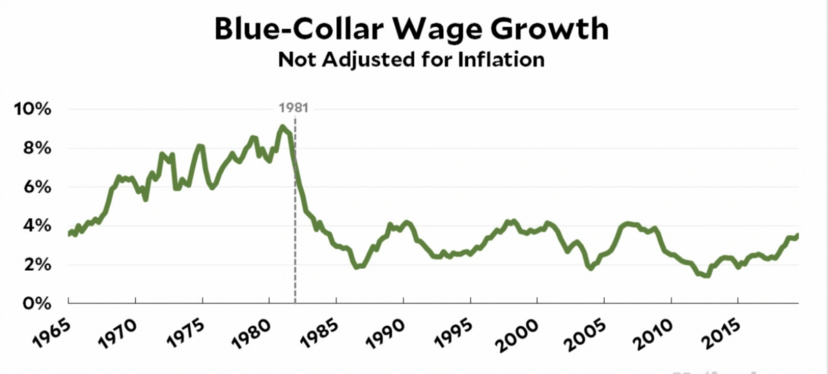

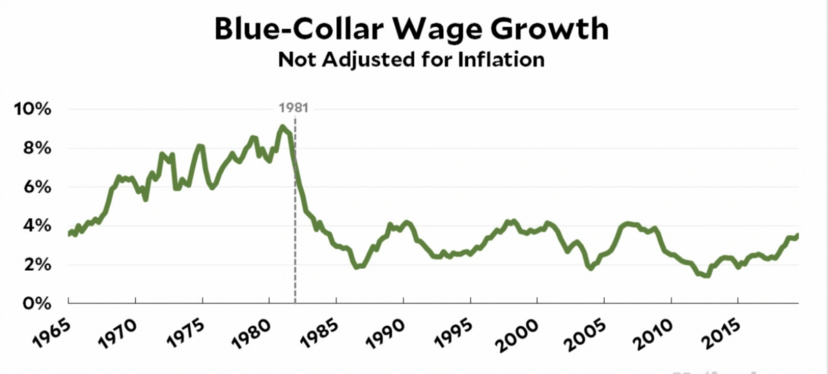

This is, again, due to, as Milton Friedman explained, Inflation Expectations. When the Federal Reserve attempted to push unemployment low through inflationary policies that boosted Aggregate Demand, they successfully lowered unemployment in the short term but caused expectations to push up nominal wages (Figure 10).

These higher nominal wages and labor costs gave rise to cost-push inflation and even an even higher inflation level than those initially caused by the rise in Aggregate Demand; however, for the reason that such a rise in the inflation level was due not to Aggregate Demand but to Inflation Expectations, or, in this case, more specifically, Rational Expectations, the unemployment level does not fall, as was typically expected by adherents of the Phillips Curve in the case of higher inflation. As the inflation level grew, expectations once more pushed up labor costs, causing the Wage-Price Spiral. This case of a higher inflation level but an unchanged unemployment level gave rise to an upwards shift of the Phillips Curve, as is evidenced in Figure 11.

The high Aggregate Demand generated by the expansionary monetary policy also served to put into effect the Long-Run Self Adjustment Mechanism, pushing the short-run output above the Long-Run Aggregate Supply, thus causing an output gap; this output gap increased strain on the labor and resource markets, driving up production costs, thus causing high prices with a simultaneous fall to production.

In the end, the Stagflation substantiated the veracity and magnitude of Milton Friedman’s ideas, namely, that of NAIRU and Inflation Expectations, and, being predicted by and solved by Friedman, also served to catapult Friedman and his colleagues at the University of Chicago to great prominence; Friedman himself became nearly as influential as Keynes had been in the early 20th Century while Monetarism became more and more authoritative in the field of economics, becoming so reputable as to be prominent enough to oppose the long-held dominance of the Keynesian School. In all, the lasting significance of the Stagflation of the 1970s lies in that it secured the robust, persisting influence of Friedman’s ideas and the Monetarist School of Economics.

Criticism of Keynesian Fiscal Policy, specifically fiscal stimulus:

Whilst the above section targets the Keynesian School’s Monetary Policy, these bottom principles dispute the Keynesian School’s Fiscal Policy, namely government spending and other stimuli to boost Aggregate Demand in case of a Recession. These policies have come under attack, most famously from the Austrian School, but in lesser degrees from the Neoclassical School of Economics and Monetarism; these are their assorted critiques.

The lessened impact of Economic Stimulus

The principle of Ricardian Equivalence holds that consumers internalize government finances when making consumption decisions. This effect is demonstrated in event that government spends or issues stimulus checks; people recognize that such spending can only be paid for by future taxation or borrowing that crowds out the bond market and drives up interest rates (see the Crowding Out Effect), leading them to avoid spending the stimulus, or, at the very least, spend less than expected, and leading to a smaller increase in demand than needed. Moreover, this theory seems to be empirically supported, with an NBER study finding that only around 40% of stimulus money issued during the COVID pandemic was spent.

The Permanent Income Hypothesis ties loosely into the Ricardian Equivalence as well, holding that the consumers spend, not entirely based on current income and wealth, but with significant consideration to expected future income and wealth. Thus, a one-time stimulus check will not cause a significant change to consumption and demand for the reason that people do not expect any change to their future income, or even go so far as to expect a decrease as a consequence of lower labor demand, thus leading to consumers avoiding the spending of stimulus checks.

The Crowding Out Effect

Another quite common critique of Keynesian stimulus is the so-called Crowding Out Effect, developed by Milton Friedman. Henry A. Hazlitt summarizes this assertion in his 1946 book Economics in One Lesson: “…every public job created…has been destroyed somewhere else.” This quote specifically mentions labor, but its meaning holds true for the entire economy. It states, in the context of using taxation to finance government spending, that all stimulus money had to have come from the private sector. Therefore, while the government purports to raise aggregate demand through taxation and spending, they were only able to do so in the first place by hurting spending and hurting aggregate demand generated from the private sector (this is also demonstrated in Frederic Bastiat’s Parable of the Broken Window, but I digress).

The result is the same in the case of government borrowing to finance stimulus: In finding lenders to fund the stimulus, the government must increase bond interest rates or lower bond prices; this only hurts bonds issued by private companies and diverts investment away from them towards the government. Again, the government’s stimulus is only able to spend and raise demand by impairing spending in the private sector, thus constituting an equal fall in demand. The worst-case scenario in this case, of course, is when private corporations raise their interest rates to compete with the government’s; this leads to an even more harmful demand shortfall in the long run.

Moral Failures of Government

A common, and more practical, critique of Keynesian control over the economy, and extensive regulation of the economy in general, is that of political infeasibility. This holds that, given power over the economy through manipulating fiscal and monetary policy, politicians will fail to use these powers as they are intended, namely, to raise Aggregate Demand in Recessions and lower Aggregate Demand in the case of Inflation; on the contrary, politicians will succumb to Populism and engage in exceedingly uneconomical policy for the sole purpose of gaining popular support and winning elections. An example of this is Richard Nixon, who, fully knowing the consequences, lowered interest rates (more specifically, he pressured the Federal Reserve to do so) and stimulated demand to produce a short-run economic boom followed by long-term high inflation; nevertheless, this was still sufficient to win him his reelection, as was his intent. When the Stagflation set in, in part due to his low interest rates, he succumbed once more to populist pressures and enacted wage and price freezes, measures supported by economically illiterate crowds but heavily advised against by economists; this is merely one example from many of politicians, tempted by populist allures, employing their economic powers harmfully for nothing more than popular support.

Keynesianism also requires high taxation and low spending, in other words, a budget surplus, at the peak of the business cycle to be able to fund stimulus and deficit spending when at the trough of the business cycle, but this has proved politically infeasible as well; the reason is simply that, even during economic booms, where it is unadvisable to do so, politicians inevitably begin to promise free spending and low taxes to economically illiterate crowds, not for the purpose of benefitting the economy in the long run, but for the sole purpose of gaining votes.

Economic Failures of Government

In addition, Robert Lucas’s famous Lucas Critique asserts that, due to the complexities and intricacies of an economy of millions of logical, forward-thinking individuals, historical, aggregate data is not sufficiently reliable as an indicator of the actions of individuals, and by extension, the elaborate economy as a whole; therefore, due to the deficiency of the information expressed through aggregate data, it would be erroneous to base large-scale economic policy decisions off of predictions developed from aggregate data or to, similarly, expect the effects of economic policy to fall in accordance with predictions based on aggregate data; this is due to the rationality and forward-thinking nature of consumers influencing them to unexpectedly change their behavior in response to policy changes, thus deviating from predictions formulated on historical trends.

Similar to the Lucas Critique, another argument formulated by Mises and Hayek of the Austrian School of Economics argues that, due to the inherent complexity and astronomical scale of an intricate network of millions of individuals, all coordinating supply and demand and allocating resources in response to pricing signals, the economy is so intricate it surpasses the administrative abilities of any number of human minds. When significant power over the economy is given to politicians and economists, as Keynesians advocate, they will inevitably prove utterly incapable of successfully guiding the economy through business cycles, as is their goal; instead, the effect of their actions, even if altruistic intent is assumed, will inevitably result in severe financial failures and cause grave far-reaching consequences to the economy. Historical examples support this view. The expanded government powers and strengthened financial authorities of the early 20th Century, for example, far from easing business cycles and periods of economic downturn, as was their intention by Keynesians, have instead mistakenly contributed to the bulk of the most ruinous recessions in modern history.

The Stagflation, being the most obvious example, was caused specifically by the Federal Reserve’s fallacious long-term targeting of the Phillips Curve. The Great Depression, as another example, was worsened by the Federal Reserve’s overly contractionary monetary policy, which caused “the total quantity of money in the United States…[to decline] by one-thirds…If [the Federal Reserve] had prevented the decline in the quantity of money, you might still have a recession…[but] it would have been over in the middle of 1930 or early ’31 at the latest, it would not have had been [a] major catastrophe…” (Milton Friedman). In the case of the Great Recession of 2008, Alan Greenspan’s policies as Federal Reserve Chairman, Lawrence Summers’s advice as Secretary of Treasury, and George H.W. Bush’s Housing and Community Development Act of 1992 have been blamed for infusing the housing market with an excess of money and credit, thus causing widespread subprime lending and later inflating the housing bubble.

Moreover, economists and politicians inevitably suffer from recognition lag, administrative lag, and response lag, institutional hindrances that cannot be rectified; these impediments severely impair the ability of their stimulus to come into effect specifically when desired when the timing of economic policies is key, and, due to this, will negatively warp the effects of economic stimulus.

Moreover, economists and politicians inevitably suffer from recognition lag, administrative lag, and response lag, institutional hindrances that cannot be rectified; these impediments severely impair the ability of their stimulus to come into effect specifically when desired when the timing of economic policies is key, and, due to this, will negatively warp the effects of economic stimulus.

With a complete criticism of Keynesian Economics above, it is only fitting to end this overlong piece with quotations from other prominent economists, describing their reasoning against the Keynesian School of Economic Thought.

“That question presupposes that economists have quite considerable insight into economic processes and great capacity to fine-tune them–for example, that we can foresee shortages and head them off…”

-Alan Greenspan when asked if more Keynesian intervention, such as from the Council of Economic Advisors, was desirable

“The miracle assumed by [Keynesians] is that government will act (1) apolitically, (2) without any of the human imperfections, myopia, and psychological quirks that (are assumed to) give rise to the market imperfections that allegedly justify government intervention, and (3) with more information and wisdom than is discovered and used in markets”

-Donald Boudreaux

[Keynesian economists]…carry too far some ideas which were good for the 1930s but which did not apply in the post-war situation

-Milton Friedman

“[N]one of us any longer accepts the initial Keynesian conclusions”

-Milton Friedman